21st Nevada Attorney General

Term: January 8, 1951 - January 3, 1955

Biography

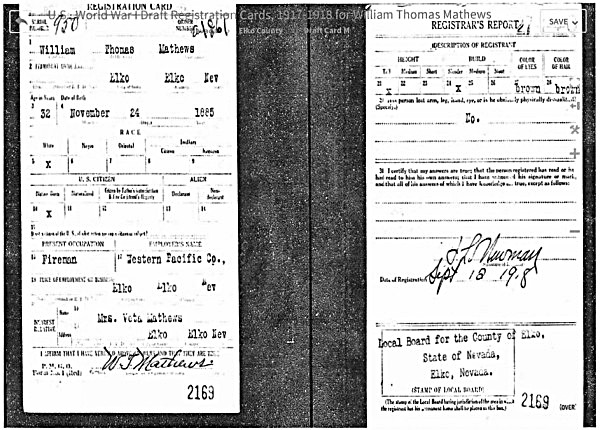

William Thomas Mathews, son of William G. and Susie Y. Middleton Mathews, was born on November 24, 1885, in La Veta, Colorado. Mathews attended Colorado Agriculture College, and in July 1910, he moved to Elko, Nevada, where he took a job as a locomotive engineer for the Western Pacific Railroad. On June 17, 1912, Mathews married Veta Emelia Mikkelsen, in Farmington, New Mexico, and on April 2, 1917, their only child, Woodrow George Mathews, was born in Elko.

After he was injured in a train wreck, William Mathews decided to go to Hamilton College of Law in Clinton, New York. He returned to Elko, started to practice law, and later, in October 1918, received his degree in Bachelor of Laws (LL.B. or B.L.) from Hamilton College.

On September 18, 1918, Mathews responded to the World War 1 draft:

Mathews, elected as the District Attorney for Elko County, Nevada, served from 1922 to 1926. In 1929 and again in 1931, the Elko County voters elected Mathews to the Nevada State Legislature as an Assemblyman to represent them. From 1929-1931, Mathews also served as the City Attorney for the City of Elko, Nevada.

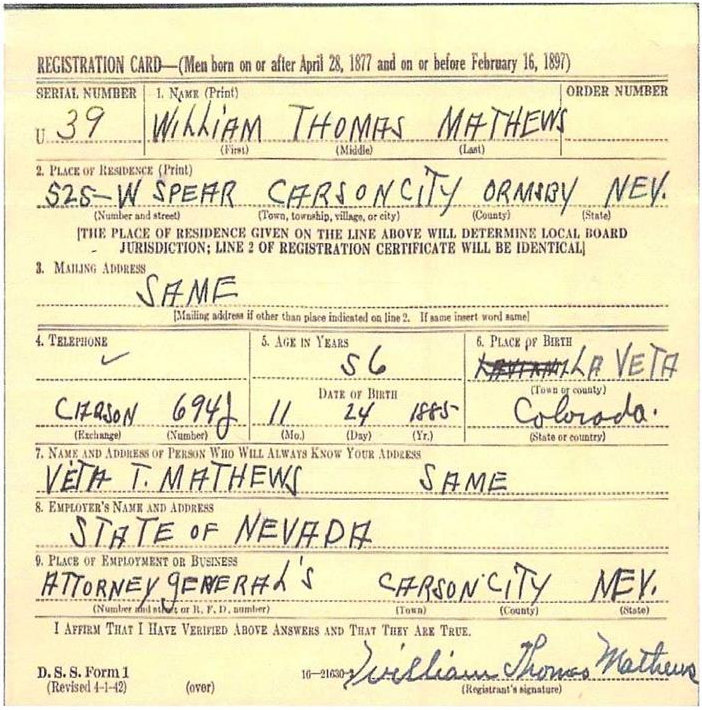

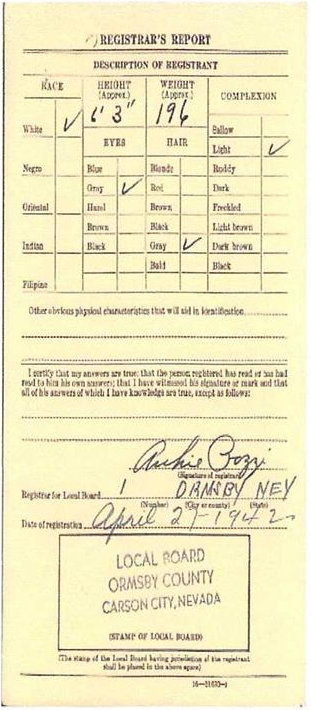

In 1942, at the age of 56, Mathews again reported for the draft—this time, for World War II.

On January 16, 1952, Mathews’ wife, Veta, died in Carson City, Ormsby County, Nevada, at the age of 68. The Reno Gazette-Journal reported that on Saturday, February 23, 2915, a “brief memorial was held for the late Mrs. William T. Mathews, wife of the attorney general of Nevada, who died recently.”[1]

On September 7, 1955, Mathews married Katharine V. M. Kennet at “the home of the bride with the Rev. Arthur V. Thurman, pastor of the First Methodist Church officiating at the informal rite.”[2]

In addition to his legal and political careers, Mathews was a member of the I. O. O. F. Lodge for 43 years, and was grand master in 1931-1932. He was chaplain for three years of the Elko Lodge of Elks and retained his card in the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers. Other memberships included the Nevada Bar Association, the American Bar Association, the Carson City Lions Club, and other organizations.[3]

Election of 1950

Long before the 1950 election, on April 1, 1931, Attorney General Gray Mashburn appointed Mathews as Chief Deputy Attorney General. He continued to serve as Chief Deputy Attorney General under Attorney General Alan Bible.

In 1945, Nevada Governor E. P. Carville and Bible asked Mathews to act as special counsel for the state of Nevada to handle Nevada’s intervention in Arizona v. California. In August 1952, the case was finally filed in the United States Supreme Court.

For more than 19 years, Mathews had served the state either as a Chief Deputy Attorney General or Special Assistant Attorney General. On May 5, 1950, the Nevada State Journal reported that Mathews announced his candidacy for Nevada Attorney General:

W.T. MATHEWS WILL RUN FOR ATTY. GENERAL, Special Assistant Files Notice of Candidacy. Announcement of the candidacy for the Democratic nomination for attorney general of William T. Mathews, special assistant to the attorney general, was made yesterday and did not come as a surprise in political circles. It is possible Mr. Mathews will have no primary opposition. This was indicated yesterday when Richard L. Waters, Jr., Ormsby County district attorney, who was expected to seek the office in the event Alan Bible did not seek reelection, said that he would support Mathews for the office. Alan Bible, attorney general for eight years, announced Friday that he would not seek reelection, and Mr. Mathews lost no time in informing John Bonner, Democratic state chairman, that he would enter the race. He will file for the office within a few days. Widely known Mr. Mathews, former district attorney of Elko county, and for 19 years attached to the attorney general's office either as a deputy or special assistant, is widely known throughout the state as he has conducted two state wide campaigns, one for attorney general and one for justice of the supreme court. A native of Colorado, he has resided in Nevada for 40 years, 21 of which were in Elko County.[4]

On November 7, 1950, Mathews was elected as Nevada’s 21st Attorney General, and of the 58,794 votes cast, Mathews (Democrat) received 32,601 votes to Royal A. Stewart’s (Republican) 26,193 votes.[5]

Major Legal Cases

As Attorney General, he continued the state’s involvement with Arizona v. California and was “associated [with] and conducted many of the major cases for the state including railroad tax suits, [and] suits against the Six Companies . . . .[6] [The Six Companies] later built Parker Dam, a portion of the Grand Coulee Dam, the Colorado River Aqueduct across the Mojave and Colorado Deserts to urban Southern California, and other large projects[7] . . . and collected many dollars in taxes for the state and counties.”[8]

Arizona v. California was a set of United States Supreme Court cases that dealt with disputes over water distribution/allocations from the Colorado River between the states of Arizona and California. The allocations had been set in the Colorado River Compact of 1922. In the suit, Arizona claimed that the state of California exceeded its share of Colorado River water, to the detriment of Arizona, and Arizona had “hoped to codify its allocation of water . . . . so that future development could take place in the Phoenix metropolitan area . . . . Nevada shared Arizona’s position about future development—Nevada expected the Las Vegas area to grow, and Nevada’s leaders feared that if Arizona successfully raised the allocation issue, Nevada could possibly lose its annual allotment, one that most experts considered quite generous .[9] [Although Nevada recognized] that a decision by the Supreme Court could have the far-reaching effect of changing the allocations originally agreed upon, Nevada . . . [still] “had to be declared a legitimate party to the suit.”[10] At the time of the intervention, Nevada only received 300,000 acre-feet of Colorado River water annually, and it wanted the Court to award approximately 555,000 acre-feet of water.[11]

In 1954, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Arizona v. California that Nevada had standing and a right to intervene in the case. See Arizona v. California, 347 U.S. 985. This was a crucial victory for Nevada, Mathews and former Attorney General Bible. Before the case was formally decided, Bible moved to a different role in a different venue—as a United States Senator[12]. “R.P. Parry reargued the cause for the state of Nevada, intervener. With him on the briefs were Roger D. Foley; Attorney General W.T. Mathews; and Clifford E. Fix.”[13] Mathews, along with Roger D. Foley, had won the lawsuit, which “at the time, attracted statewide attention”.[14] The Arizona v. California trial lasted from June 14, 1956–August 28, 1958, and it wasn’t until March 9, 1964, that the United States Supreme Court issued its final decree[15] “which specified the quantities and priorities of the water entitlements for the States, the United States, and the Tribes”. Arizona v. California, 376 U.S. 340.[16] The Court recognized that the Colorado River Compact provided for a division of water between Upper Basin States (Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, and New Mexico) and the Lower Basin States (Arizona, Nevada, and California). However, the Compact did not provide for a further subdivision of water among the three Lower Basin States. The Court concluded that the Boulder Canyon Project Act, which authorized the construction of the All-American Canal and other Colorado River diversion works, accomplished that task.”[17] Arizona v. California was one of the longest-running water rights cases, and although the original case began in the United States Supreme Court in 1952, other cases with the same name were decided in 1931, 1934, and 1936. Subsequent cases were filed in 1964, 1966, 1979, 1983, 1984, and 2000.

Another important case to Nevada is State ex rel. Mathews v. Murray, 70 Nev. 116, 258 P.2d 982 (1953) that Mathews filed in 1952. This case dealt with the state’s separation- of-powers doctrine and has been addressed by at least three of Mathews’ successors, Harvey Dickerson, Robert List, and Brian Sandoval. In a Las Vegas Review Journal editorial titled “Power Play: State’s separation of powers doctrine effectively ignored”, Vin Suprynowicz, an assistant editorial page editor wrote:

As this provision was understood from 1864 until at least 1964, no teacher or other employee retained or employed by a government school or college or university that receives substantial state money, no police officer or firefighter—no one who works for any other branch of government at any level or in any capacity—was allowed to hold elected public office in Nevada, and especially not seats in the Legislature. ‘The concentration (of the powers of government) in the same hands is precisely the definition of despotic government,’ wrote Thomas Jefferson in 1782. ‘It will be no alleviation that these powers be exercised by a plurality of hands, and not by a single one. One hundred and seventy-three despots would surely be as oppressive as one.’

The action, Mathews told the court, was not filed in order to punish the former state senator but to establish a legal precedence in order to provide a guide for the state government and its commission and department heads in the future.

Mathews, a Democrat, told state Sen. John Murray of Eureka County that he couldn’t continue working for the Department of Motor Vehicles while serving as an elected lawmaker. “Executive class includes all persons who have functions in the administration of public affairs,” Mathews wrote. He contended that Murray was holding the post as a director of the Public Service Commission's driver’s license division in violation of the state constitution. Mathews charged Murray, a Republican, was holding two positions in the state government, one in the executive branch and one in the legislative. The attorney general pointed out the constitution states that no person exercising powers of one branch of government shall exercise any function belonging to either of the other branches unless expressly permitted to do so by law. It was further alleged that Murray had served in a legislature which had increased the pay of the head of the driver’s license division. The attorney general asked the bench to decide "if the constitution means what it says." Mathews, however, did not ask the court to recover funds paid Murray. [18]

In 1954, Mathews offered the opinion that two Republican state legislators, Senator Edward Leutzinger and Assembly member Baptaste Tognoni, were not entitled to leaves from their state highway department jobs during the legislative session saying, “[w]e think such practice would ignore if not in fact be violative of the above quoted constitutional provisions.

Nevada’s next attorney general, Harvey Dickerson, a Democrat, initially saw the provision the same way. He ruled [that] a member of the state Assembly could not at the same time hold a position in local government. Because counties, cities, and school districts are creatures of the state, he wrote (citing some of the same precedents as Mathews); an assemblyman could not also receive remuneration as an employee of the Hawthorne Elementary School District. “The school districts are political subdivisions of the state government and part of the executive branch,” Dickerson wrote. “An employee of the school district is exercising a function appertaining to the executive branch. If that employee is at the same time an assemblyman, the activity is in conflict with the above quoted constitutional provision.”

Dickerson noted legislative service is not really just a few months every two years; a lawmaker can be called into special session at any time and frequently serves on interim committees “all during his two-year term.” The question was raised whether the assemblyman’s school district job—janitor—really constituted a “public office.” The attorney general responded that the separation-of-powers prohibition specifically applies to mere employment in one branch of government if the person exercises powers in another. But in 1967, for reasons never disclosed, Dickerson changed his mind, holding a local fire chief (from the city of Sparks) could serve as a state senator.

By 1971, under newly elected Attorney General Robert F. List, the lid was blown off the separation-of-powers doctrine completely. He held that a person could “exercise powers” as a legislator so long as you didn’t “exercise powers” in one of the other branches—in essence, so long as you “just worked there.”

In 2004, Attorney General Brian Sandoval issued an opinion holding that state workers should not be allowed to sit in Carson City. But it has never been tested in the courts and is widely ignored.

In effect, this means virtually any government employee short of the governor and a few other statewide elected officials could probably serve simultaneously in the Legislature—and that legislators, once elected, can be offered jobs and thus “captured” by virtually any government agency at any level—something that now happens with some frequency.

Thus was the protection destroyed, leaving Nevadans in a position where our employees are now our bosses, voting themselves largess from our checkbooks.

[I]n January 2003, Steven Miller of the Nevada Policy Research Institute wrote: “The successful neutralization of the Nevada Constitution’s separation-of-powers clause increasingly gives citizens of the Silver State a skewed and distorted political system. People who are supposed to be our employees now increasingly write the laws and tell the rest of us what to do . . . .[19][20]

[Emphasis added]

Office Administration and Duties

The Nevada Attorney General’s operating budgets for the 1951–1953 and 1953–1955 state biennial fiscal periods were as follows:

1951–1953 Budget

|

$58,700

|

|

$11,200

|

Salary of the Attorney General

|

|

$42,500

|

Salaries (Deputy Special Assistant Attorney General,

extra Deputy Attorney General, Chief Clerk,

Clerk-Stenographer, extra clerical)

|

|

$1,500

|

Travel (in state and out-of-state)

|

|

$3,500

|

Office Supplies and Equipment

|

|

|

|

|

| 1953–1954 Budget |

$63 569 |

|

| |

$14,000 |

Salary of the Attorney General

|

|

|

$39,516 |

Salaries (Chief Deputy, Deputy Special Assistant

Attorney General, Chief Legal Stenographer; including

possible severance and sick leave benefit of 6 months

@ $288 per month)

|

|

|

$1,750 |

Travel (in state and out-of-state)

|

|

|

$5,559 |

Office Supplies and Equipment

|

|

|

$229 |

Benefits: Industrial Insurance Premiums

|

|

|

$2,137 |

Benefits: Retirement Contribution

|

|

|

$378 |

Benefits: PERS Assessment

|

|

|

[$50,000] |

Legal Costs for the Colorado River lawsuit - $50,000[21]

|

The 1951 Nevada State Legislature did not add any additional duties to the Nevada Attorney General’s Office.

The 1953 Nevada State Legislature added the following duties to the Nevada Attorney General’s Office:

The Attorney General “. . . shall be counsel and attorney for the Department of Highways in all actions, proceedings, and hearings . . . .” (Statutes of Nevada 1953, Chapter 133, Section 4½, Page 145).

The legislature created the Nevada Oil and Gas Conservation Commission with the Attorney General charged to be its legal counsel (attorney). (Statutes of Nevada 1953, Chapter 202, Section 3.3, Page 238). (Statutes of Nevada 1953, Chapter 202, Section 12.4, Page 250).

The Attorney General was directed to legally intervene in the lawsuit between the State of Arizona and the State of California relative to the waters rights of the Colorado River (case was pending before the US Supreme Court) (Statutes of Nevada 1953, Chapter 214, Inclusive, Pages 267–268).

The legislature amended 1947 Statutes of Nevada, Section 88 to read (regarding the Industrial Insurance Commission ) “. . . the Attorney General is to give his legal opinion in writing as to the validity of any act or acts of any state or city or school district, irrigation or drainage district under such bonds are issued . . . .” (Statutes of Nevada 1953, Chapter 223, Section 88, Page 303).

Epilogue

In April 1954, Mathews “made it official over the week end that he would not be a candidate for re-election.” In a letter to Keith Lee, Democratic state chairman, Mathews said that after 23 years as a state attorney general or assistant attorney general, ‘I feel the time has come when I must look to my own welfare to a certain extent for the years of my life now remaining.’"[22]

Mathews continued to practice of law, and on August 1, 1969, he died in Reno, at the age of 83.

Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 6, by Senators Brown, Foley, Wilson, Young, and Pozzi, File Number 27, was adopted by the legislature on July 26, 1971. The letter, sent to Mathews’ wife Katharine, memorialized the late assemblyman and former attorney general:

Whereas, The legislature of the State of Nevada has learned with great sorrow of the passing of William Thomas Mathews, a devoted public servant; and

Whereas, Mr. Mathews was an able lawyer, being admitted to the State Bar of Nevada in 1918 and practicing law in Elko, Nevada; and

Whereas, Mr. Mathews early in his legal career demonstrated his willingness to give himself to public service, serving as Elko County district attorney from 1922 to 1926 and Elko city attorney from 1929 to 1931. In 1928 and again in 1930 he was elected to the Nevada assembly; and

Whereas, In 1931, Mr. Mathews became chief deputy attorney general of the State of Nevada, a post he held until 1950, when he was elected attorney general, an office he held for 4 years; now, therefore, be it

Resolved by the Senate of the State of Nevada, the Assembly concurring, That the members of the 56th session of the Nevada legislature express their sincere and deep sorrow to the surviving family of the late Mr. William Thomas Mathews, and be it further

Resolved, That a copy of this resolution be prepared and transmitted forthwith by the legislative counsel to the surviving family of Mr. Mathews.

[1] Reno Gazette-Journal, Reno, NV, Feb 23, 1952, p. 5.

[2] Nevada State Journal, September 11, 1955, p 19.

[3] Nevada State Journal, Reno, Nevada, May 5, 1950, p. 3.

[4] Nevada State Journal, Reno, Nevada, Friday May 5, 1950, p. 3.

[5] Political History of Nevada, 2006, p. 385.

[6] Six Companies, Inc. was a joint venture of eight construction companies (including Kaiser and Bechtel, to name a few) that was formed to build the Hoover Dam on the Colorado River in Nevada and Arizona. Henry J. Kaiser insisted that the joint venture be called Six Companies, Inc., a name he borrowed from the tribunal before which the Chines tongs, the equivalent of the Mafia families, took their grievances. Reisner, Marc (1993). Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water. Penguin Books. p. 127.

[7] Alan Brinkley. The Unfinished Nation, A Concise History of the American People, Vol. 2, 6th Edition, Study Guide, Content Technologies, 2014, pp. 31-32.

[8] Reno Gazette-Journal, Reno, NV. Friday, August 11, 1950, p. 13.

[9] The Maverick Spirit: Building the New Nevada, edited by Richard O. Davies, 1999, pp. 103-104.

[10] The Maverick Spirit, pg. 103-104.

[12] The Maverick Spirit, p. 104.

[14] Reno Gazette-Journal, Reno, NV, August 11, 1950, p. 13.

[15] The decree stated that “[w]ithin two years from the date of this decree, the States of Arizona, California, and Nevada shall furnish to this Court and to the Secretary of the Interior a list of the present perfected rights, with their claimed priority dates, in waters of the mainstream within each State, respectively, in terms of consumptive use, except those relating to federal establishments. Any named party to this proceeding may present its claim of present perfected rights or its opposition to the claims of others.” Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School. www.law.cornell.edu. Accessed June 22, 2017.

[16] www.law.cornell.edu, Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School. Accessed June 22, 2017.

[18] Nevada State Journal, Reno, Nevada, May 21, 1953, p. 8.

[19] In the 1999 Nevada Legislature, 44 percent of the members of the state legislature—28 of 63—also held government jobs or were married to government employees. In the 2001 Assembly, a public employee occupied every position of power.

[21] Statutes of Nevada, 1953, Chapter 214, pp. 267–268.

[22] Reno Gazette-Journal, Reno, Nevada, April 12, 1954, p 13.